CIRCULAR

TIMES

CIRCULAR

TIMES

Hexagon, Solstice, Kiva,- Chris Hardaker - A review of geometric design types found in Chaco Canyon kivas, a rather remarkable coincidence between design and astronomy is discussed.

An International Networking Educational Institute

Intellectual, Scientific and Philosophical Studies

CIRCULAR TIMES HOMEPAGE CONTACT SITE NAVIGATION HIGHLIGHTED TABLE OF CONTENTS

THE HEXAGON, THE SOLSTICE AND THE KIVA

by Chris Hardaker, M.A. Anthropology

© 2003

Note: These graphics would not reduce well so you could read the text, the text would blur. Depending upon what browser you are using, the written text of the article may be bumped all of the way to the left. Sorry for the inconvenience, but it was either reading the graphics and understanding them or not. So, I had to make a choice. I chose to keep the graphics readable and comprehensible. [Colette]

The Hexagon and the Solstice

ABSTRACT

After a review of geometric design types found in Chaco Canyon kivas, a rather remarkable coincidence between design and astronomy is discussed. Classical, or sacred, geometry can construct the perfect hexagon from the radius of a circle. A six-fold division is common among the smaller “clan” kivas. The 60-degree central angle of the hexagon mirrors the 60-degree azimuth of the Winter and Summer Solstices in Chaco Canyon. The ramifications of these two facts play themselves out in the dynamic symmetry of the great kiva of Chetro Ketl.

1. INTRODUCTION

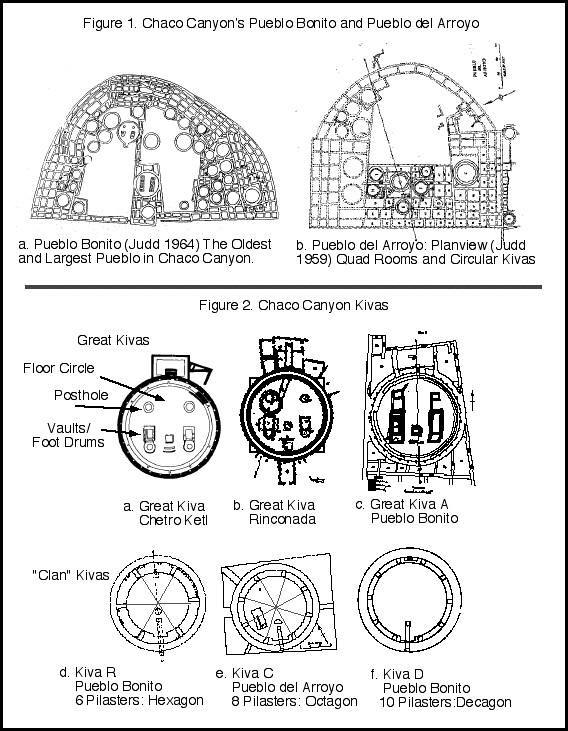

Walking among the ruins or

gazing at photographs of the pueblos in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, you will

notice the interplay of squares and circles. Squares, rectangles, and asymmetric

quadrilaterals play themselves out in the rooms and room blocks. Circles are

reserved for kivas, both great and clan kivas (Figure 1). It is a striking,

obvious and repetitive opposition practiced throughout the Anasazi Southwest

from about 600 -1300 AD.

[[Figure 1. Chaco Canyon’s Pueblo Bonito and Pueblo del Arroyo]]

What was the nature of this represented opposition? Was it even regarded as an opposition by the Anasazi? Could it represent a sequence like circle is first, square is second, or vice-versa? If opposition was the meaning, did squares and circles represent secular and sacred, respectively? Earth and Spirit? Were these held in a gnostic kind of opposition whereby the two were regarded as irresolvable as oil and water? Or was it an opposition that could be, indeed, needed to be resolved -- hence more of a Taoist (i.e. yin-yang) approach to existence?

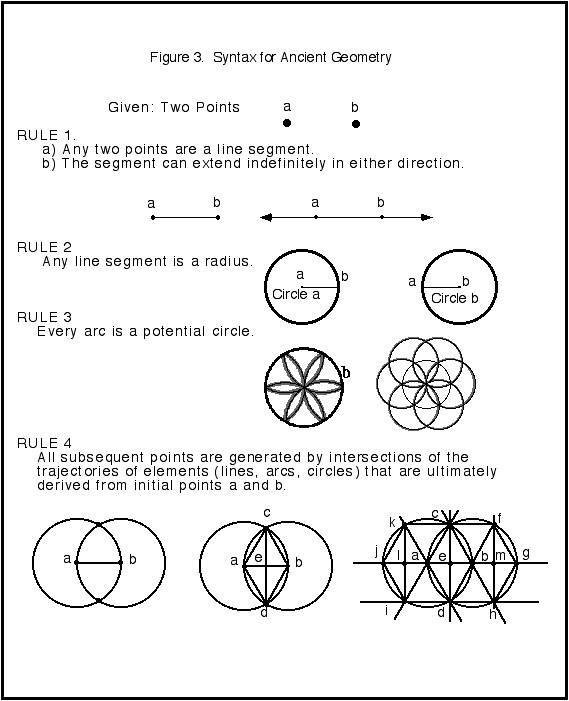

Among archaeologists, artists, and anyone who has ever thought about these buildings, kivas have been routinely attributed sacred, ceremonial status, while the quad shapes (roomblocks, material storage areas) signify economic and everyday living kinds of activities. These strict attributions have been seriously questioned since “everyday” activities may have transpired in some of the smaller “clan” kivas (see Lekson Refs). One thing we are all pretty sure of however: the great kivas were ceremonial, religious structures (FIGURE 2 a-c).

[[ Figure 2. Chaco Canyon Kivas ]]

Meaning is a tricky thing for archaeologists since we have no one to talk to, and the native inheritors of the Anasazi territory may have their own ideas. There is no way to be sure. As an archaeologist, there was a need to get closer than the cultural relativity of symbolic representations. Instead of meaning, I chose to examine commonalities of structures. What was the structural nature of the circle-square opposition?

2. BACKGROUND

Interest in the architectural nature of the Anasazi ruins of Chaco Canyon and other Puebloan settlements has continued for decades, with most investigators limiting themselves to discussions on materials used and the structures themselves (Doyel 1992; Fowler and Stein 1992; Hudson 1972; Lekson 1984; McKenna and Truell 1986; Stein et al 1996; Reid and Stein 1998; Stein et al 1996; Williamson 1983). With respect to design, two leading scholars on Chacoan architecture, John Stein and Steve Lekson, share a concern for recovering the general meaning of the built-form phenomena found in the canyon. "What are the basic parts of the architectural composition and what are the critical issues that organize them?" (Stein and Lekson 1992:91)

If we are ever to understand Chaco, we must first endeavor to understand the set of "rules" (syntax) that structure the basic architectural vocabulary of the Anasazi-built environment. This is design. A dictionary definition of design is ‘the arrangement of parts of something according to a plan.’ In contemporary architectural design, building morphology (the design solution) is a mosaic of issues synthesized into the whole (Ibid: 94).

They argue for architectural specialists charged with designing, supervising and sponsoring the efforts. "‘Image’ is a critical function of ritual architecture, and is attained through special techniques that collectively compose a ‘sacred technology’." (Ibid) What this "sacred technology" is, however, remains undefined. Lekson (1988, 1989) even questions the ceremonial role of the smaller clan kivas given the evidence in some that they may have been used for dwellings. With respect to the great kivas, however, there is virtual unanimity regarding their probably sacred functions.

Geometric motifs, designs, architectural styles are rife throughout the Native America, and in the United States, the Southwest seems to have been absolutely obsessed by them. Abstract geometric designs, generally a variation of one of the regular polygons, are everywhere: scratched into cliffs, woven into textiles, painted on ceramics. Attempts to understand the importance of geometry in the surviving cultures of Native Americans has been limited to a few works (Paternosto 1997; Pinxten 1983, 1987). None describe the knowledge system used to produce the designs.

Was there a common geometry to all cultures? Or, was this a tradition of each culture, unconnected to those across the river, across the country? How did these abstract forms come to attract so much attention? To deal with these questions effectively, an objective, scientific model and method would be required. Both were found in the spatial paradigm of ancient geometry (Kappraff 1991; Nicholsen et al), also referred to as classical (Smith 1951) and sacred geometry (Lawlor 1995). Design styles in a workbook form is available in Seymour 1988.

3. ANCIENT GEOMETRY: And Design Standard

Rik Pinxten (1983, 1987)

provides the sole ethnographic work that examines this kind of knowledge among a

non-Pueblo culture, the Navajo. The Navajo have hexagonal and octagonal homes

called hogans. This kind of geometry could come in handy when laying down the

logs. Still, there is a tendency for the Navajo and other southwestern tribes to

not talk about it much. Therefore, adopting a methodological framework based on

the principles of ancient geometry for investigating Chaco kivas seemed like a

fairly objective way to go (Hardaker 1998a, 1998b, 2001). Marshall (1987)

applied similar priniciples to the Hopewell and Adena moundbuilders in the

eastern United States. Closs’ Native American Mathematics (1986)

included interesting information, but did not discuss ancient geometry as a

working system.

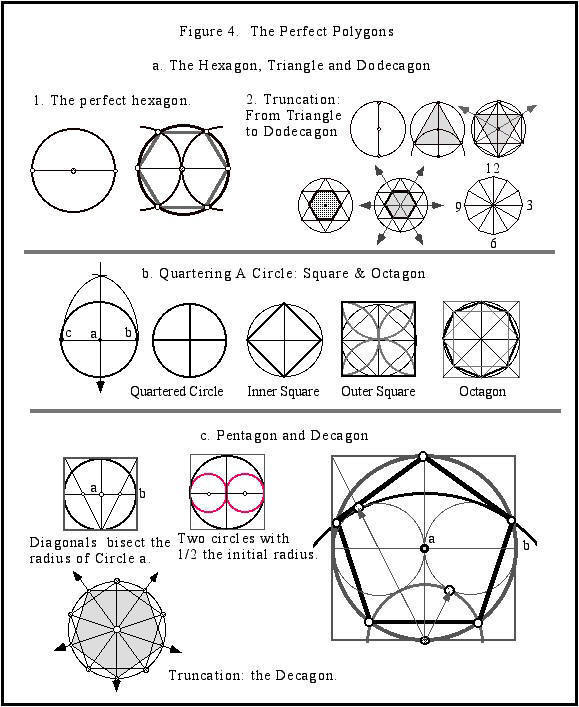

Ancient Geometry can be defined as a brand of geometry that begins from scratch. These operations are united by a simple, largely self-evident syntax, or rules of operation (Figure 3). Nicholsen, et al (1998) provides an excellent introduction and discussion of the taxonomic limitations of this connect-the-dot framework, as do Blackwell (1984) and El Said and Parman (1976) in their introductory chapters. Seymour (1988) is an excellent primer for geometrical designs using ancient principles.

[ Figure 3. Syntax for Ancient Geometry ]

Two points (a, b) represent the beginning of Nature’s geometry. The distance between can be of any length. The two points means they can funtion as a line segment, and determine the direction (orientation) of a line of indefinite length. Two points also specify the radius of a circle. Each point can serve as a center of two circles sharing the same radius.

Drawing both circles, they intersect at two points. These points derive from the operation of the shared radius. Each new point becomes a potential center sharing the same radius as the initial circles. Kept up, a six-petalled design occurs within the circles traditionally known as the Flower of Life (Figure 3, Rule 3). It is a spatial matrix. Everything available in ancient geometry is present in this pattern and its ramifications.

The six-fold division is an embedded relation between the radius and circumference of every circle. It may figure into why every snowflake design derives from the hexagon. If they had taught this to me in the 4th Grade, I may have gotten interested in math.

The limitations imposed on

the individual’s choices and actions insure a non-random unfolding of shapes and

increasing number of intersections. All intersections generated by lines or arcs

are “legal” points insofar as they are naturally occurring, that is, a

consequence of the initial operations. The fact that these shapes play out the

way they do means that this is a natural system. We add nothing; we can only

attempt to be precise. Ancient geometry thus qualifies as a science of space. It

was never invented; rather, it constitutes a discovery, like gravity and fire.

Your keys are the compass and ruler, or on larger scales, stakes and stretched

cords.

Polygon construction is a key function of this system. Briefly, the perfect triangle, square and pentagon are the primary constructions (Figure 4). From these basic forms arise their truncated derivatives. From the triangle (3) arises the hexagon (6) which gives birth to the dodecagon (12), onto 24-gon, 48-gon, and so on. The square (4) gives rise to the octagon (8) and then the 16-gon. The pentagon (5) provides the points for the decagon (10), the 20-gon, and so on.

[[ Figure 4. The Perfect Polygons ]]

4. KIVA GEOMETRY

The first clue that a form of classical geometry was at work came from the smaller “clan” kivas (Figure 2d-f). Clan kivas are often accompanied by divisions (pilasters) around their circumferences. Pilasters are divisions that function as beam supports, and later fashioned into columns. Equidistant pilasters served as beam supports for the internal cribbed (hogan-like) structure. Later, they changed into vertical columns. In Chaco Canyon, the divisions are precisely spaced, and serve as handy devices to relocate a kiva's center -- a feature almost never represented in kiva floor features. Circular divisions of 6, 8, and 10 mirror the hexagon, octagon and decagon. No other division types occur in Chaco Canyon, i.e. 7, 9, 11, 13.

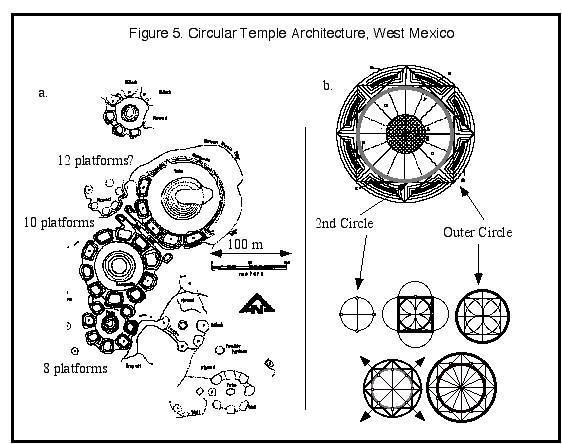

A thousand years earlier in

West Mexico (Weigand 1995, 1996), another civilization built circular temple

structures with four, six, eight, ten, possibly twelve divisions around a

central temple, measuring over 100 meters in diameter (Figure 5).

Again the absence of the odd numbered divisions

(beyond the pentagon) seemed to suggest this constructive tradition was also

present. Further, the template given for one of the temples reflects the

square-circle opposition, with alternating circles and squares. This is an

alternation factored on the proportional constant of √2 (Lawlor 1995: 23-31).

A thousand years earlier in

West Mexico (Weigand 1995, 1996), another civilization built circular temple

structures with four, six, eight, ten, possibly twelve divisions around a

central temple, measuring over 100 meters in diameter (Figure 5).

Again the absence of the odd numbered divisions

(beyond the pentagon) seemed to suggest this constructive tradition was also

present. Further, the template given for one of the temples reflects the

square-circle opposition, with alternating circles and squares. This is an

alternation factored on the proportional constant of √2 (Lawlor 1995: 23-31).

CAPTION Figure 5. Circular Temple Architecture, West Mexico

a) Guachimonton precinct, Teuchitlan, Jalisco (Weigand 1996: Figure 4). Platform arrangements echo those of kiva pilasters on a much larger scale.The large northern complex may have had twelve platforms prior to erosion.

b) 4-8-16:

Weigand's model for circular temple complexes in West Mexico (1996: Figure 7). A

quartered circle provides points for outer square, and a radius is extended to

its corner to make the outer circle. Intersecting squares provide the points for

the eight additional sections. ]]

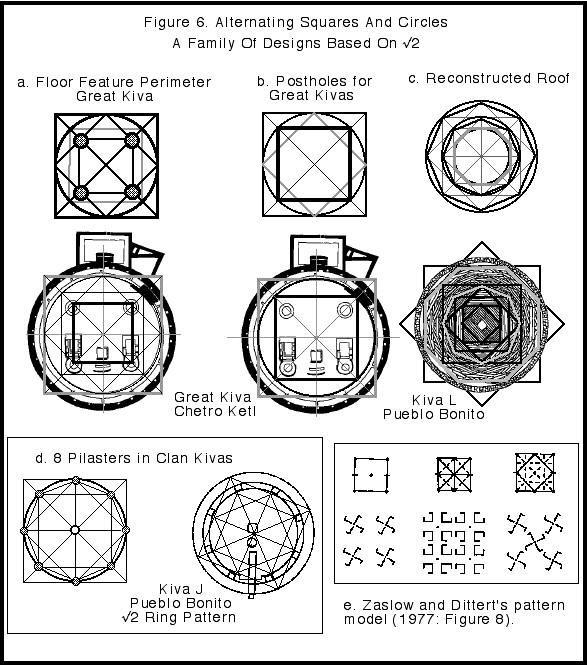

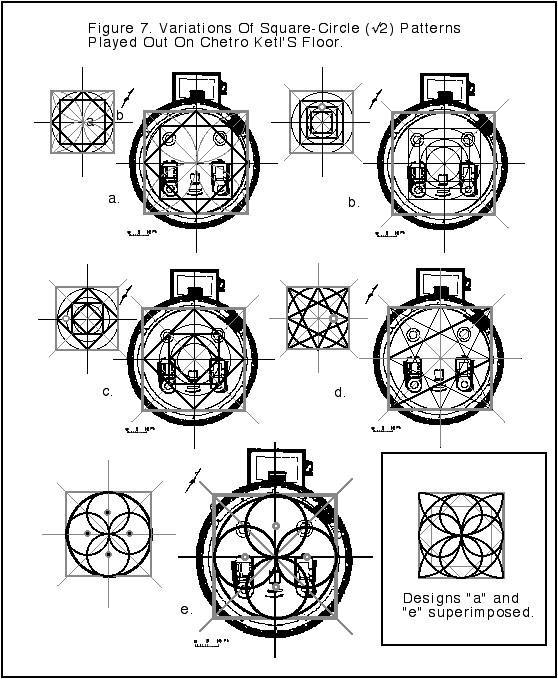

The suite of floor features in great kivas also seemed to reflect an internal opposition of square and circle. The vaults and the postholes seemed to denote square relationships. Using the traditional device of placing the subject to be studied within a square (as in Brunes 1967), the floor circle’s outer square was superimposed on great kivas. The ramifications of this construct are varied, yet each seems to mark out the organizational features: the perimeter of the entire suite of features, and the designation of post holes (Figures 6, 7). The perimeter of the floor features appears to be based on the inner square of the floor circle. The post holes are marked out by the next lower scale of the circle-square relation. Similar pattern are also apparent in kivas with 8 pilasters and in decorative designs throughout the American Southwest.

Figure 6. Alternating Squares And Circles

Figure 7. Variations Of Square-Circle (√2) Patterns Played Out On Chetro Ketl's Floor.

5. THE HEXAGON, THE SOLSTICE AND THE KIVA

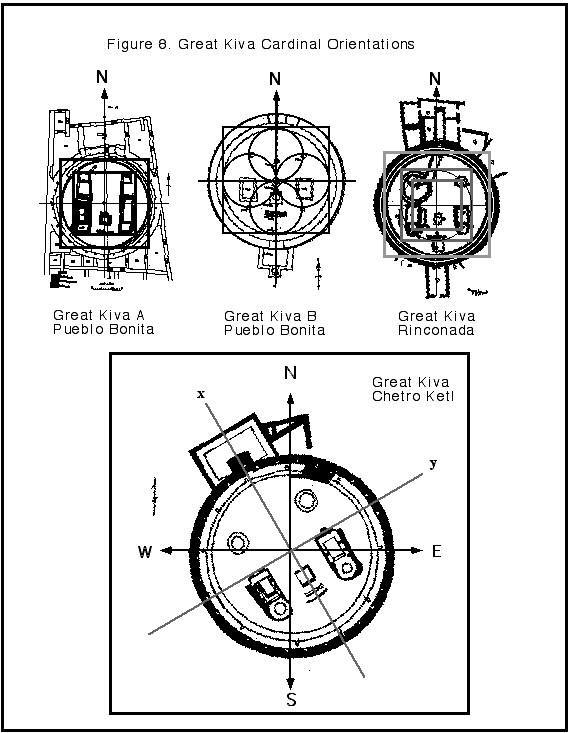

Up until this

point, all great kivas have been represented along their binary axes. In most

cases, their binary axes were aligned with the cardinal axes, conforming to

north-south and east-west directions (Figure 8). The great kiva of Chetro Ketl

was the exception to this rule. Why was it not like the others?

Figure 8. Great Kiva Cardinal Orientations

Archaeo-astronomy, the study of ancient astronomical practices, has been a popular topic among astronomers, architects, artists and archaeologists alike (Carlson and Judge 1983). Chaco Canyon was one of the primary regions where this multi-disciplined pursuit has found success over the past decades. (Williamson 1983, Soffaer 1996). I was not unfamiliar with it, but design geometry was unrelated to astronomy, or so I thought.

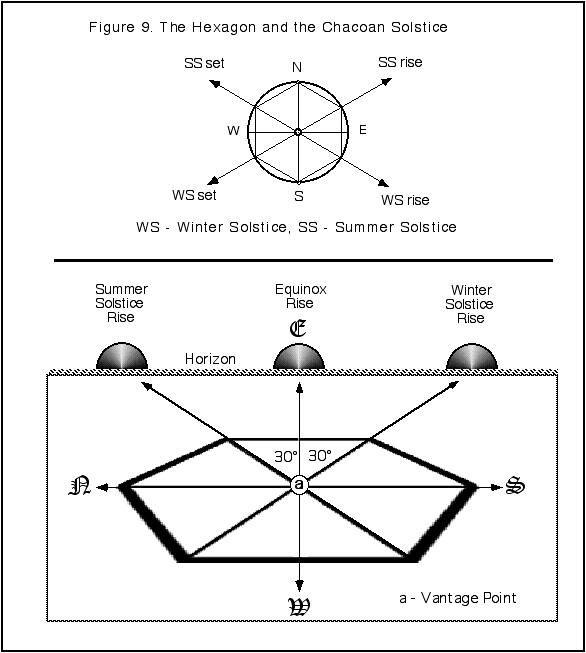

Chaco Canyon’s solsticial suns rise and set along the horizon like they do along any horizon. In the northern hemisphere, the summer solstice rises and sets north of the east-west line, and in the winter it sets south of this line. Depending how far north of the equator you are standing, there is an constant angle along this horizon that specifies the azimuth of the rising and setting suns at your location. At Chaco Canyon the azimuth is 60.4 degrees, virtually the central angle of the hexagon. Along an east-west line, the suns rise and set 30.2 degrees north or south of that line. The setting sun takes up about one-half degree on the horizon, making the azimuth a physical reflection of the central angle of the hexagon (Figure 9).

CAPTION

Figure 9. The Hexagon and the Chacoan Solstice

a. Plan

view. Oriented along a north-south axis, the hexagon's two remaining axes line

up with horizon points marking the risings and settings of summer and winter

solstices. This is true for any point on the ground in the Canyon.

axes line

up with horizon points marking the risings and settings of summer and winter

solstices. This is true for any point on the ground in the Canyon.

b. Ground View. The 60.4° Azimuth at Pueblo Bonito/Chaco Canyon and the 0.5° diameter of the sun on the horizon makes the hexagon an effective tool for solsticial investigations in the canyon. ]]

While there is a very good chance the Anasazi had no concept of degrees: 1) they did know the cardinal directions, and; 2) they probably knew the hexagon given the common 6-fold division of clan kivas found throughout the Anasazi realm and in countless designs decorating basketry, textiles and ceramics.

Did the Anasazi make the connection with the solstices and the hexagon’s central angle?

It is doubtful we will ever know since the Anasazi architects have all passed on. Still, since the azimuth remains the same as when the structures were built, the hexagon template is a practical and objective scientific tool for assessing solsticial relationships in the Anasazi realm. To examine solsticial relationships among the Chaco Anasazi buildings (kivas, pueblos), all one has to do is orient the kiva along the north-south axis, and then superimpose a hexagon along the same north-south axis. The hexagon’s crossing axes specifies the Summer Solstice setting/rising points on the horizon and the Winter Solstice setting/rise on the horizon.

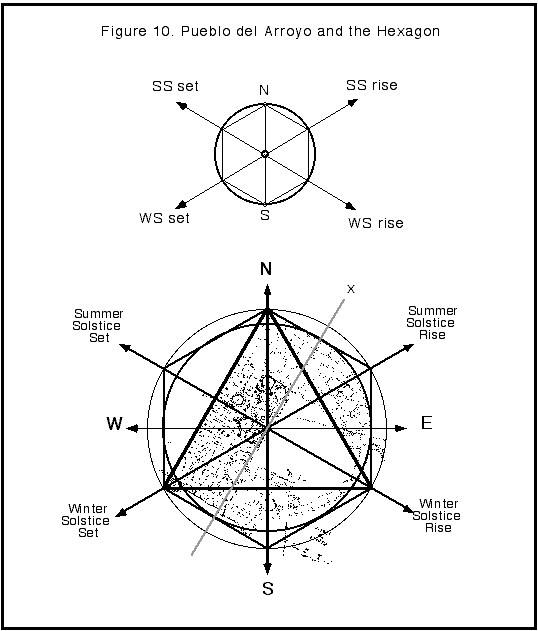

Figure 10 shows this model applied to the entire planview, or “footprint” of Pueblo del Arroyo. Its binary perspective is shown in Figure 1. Here, the orientation has shifted to align the footprint to its cardinal axis. What was once a binary axes falls along the same axis specifying the Summer Solstice setting and the Winter Solstice rise.

(CAPTION) Figure 10. Pueblo del Arroyo and the Hexagon.

The hexagon model is

superimposed on "footprint" of Pueblo del Arroyo. The footprint is oriented

along cardinal lines and then superimposed by a hexagon oriented north. A binary

axis of the footprint aligns with the axis linking the Summer Solstice Set and

Winter Solstice Rise

The hexagon model is

superimposed on "footprint" of Pueblo del Arroyo. The footprint is oriented

along cardinal lines and then superimposed by a hexagon oriented north. A binary

axis of the footprint aligns with the axis linking the Summer Solstice Set and

Winter Solstice Rise

With the exception of Chetro Ketl, the other great kivas in the Canyon were oriented along their cardinal axes. Williamson (1983:100-103) did locate niches (or ports) built into the walls of Rinconada’s great kiva that corresponded with the rising Summer Solstice. These additional architectural features had no effect on the great kiva’s overall cardinal orientation.

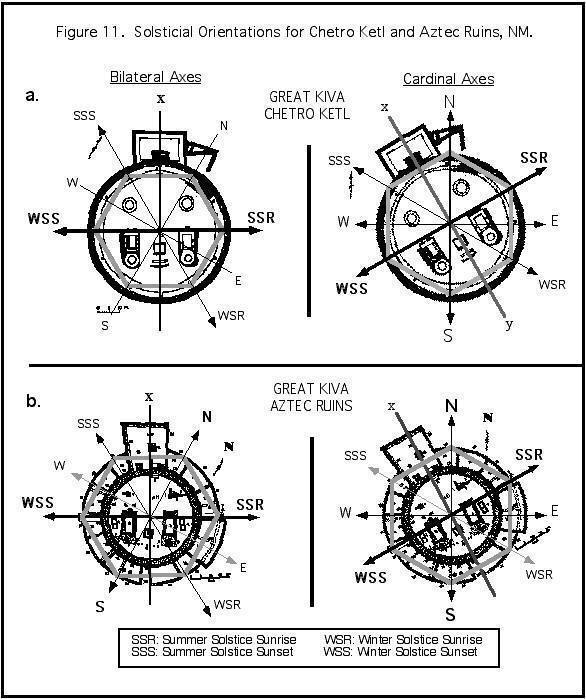

Orienting Chetro Ketl on a north-south axis, a hexagon was superimposed with its diameters drawn to approximate the solsticial azimuths (Figure 11). One of its binary axes aligns with the Summer Solstice rise and Winter Solstice set axis of the hexagon model. In Chaco Canyon, this was the only great kiva so aligned. Another great kiva so aligned was found about a hundred miles north of the canyon at a place called Aztec Ruins National Monument in Aztec, NM. The Aztec Ruins are the remains of a large Anasazi settlement with a great kiva. Using the original foundations, it was reconstructed into a walk-through example of what a great kiva might look like when it was first built. The Aztec Ruins great kiva was aligned in exactly the same way as the

Chetro Ketl kiva. Their bilateral symmetry shares an orientation with the Summer Solstice rise and Winter Solstice set axis.

Figure 11.

Solsticial Orientations for Chetro Ketl and Aztec Ruins NM (b) are shown with

respect to their bilateral and cardinal orientations. A superimposed hexagon

coincides with their north-south axes. The vault axis, a binary axis, coincides

with the Winter Solstice Sunset- Summer Solstice Sunrise axi s.

s.

6. QUESTIONS

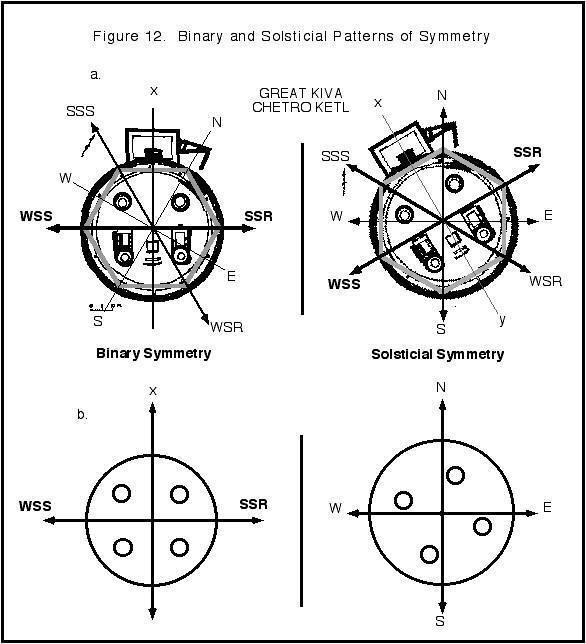

My interest in geometry has been wholly focused on structural designs using ancient geometry principles. Symmetry, in and of itself, is still quite unfamiliar, other than its natural expressions embedded throughout the constructions. Something was observed during the course of the solstice investigations that cannot yet be accounted for, a phenomena that would appear to be related to the study of symmetry and motion. Structural investigations are spatial investigations. Time and motion never entered into the phenomena I was looking at until the solstice aspect was examined. The axes of the binary and solsticial models shift in relation to the kiva’s postholes (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Binary and Solsticial Patterns of Symmetry

There is no solsticial shift in the other great kivas aligned with the cardinal axes.

Is this

“shift” accidental or unintentional? Was this shift unrecognized by the

priest-architects? If intentional, what could it represent? Is it a dynamic

symmetry related to the cycles of the sun? Is there a motion element involved in

this transformation? Is it related to time and dimension? Is it a symmetry that

turns up elsewhere in the Anasazi culture area? None of these questions have yet

been answered since symmetry has not been a primary focus. It is hoped that its

presentation here will bring some needed insight to the phenomena.

Given the sophisticated nature of Anasazi science, astronomy and engineering, is it proper to conclude they would not have noticed this shift in symmetry? Or can it be written off as an example of archaeological Rorschach?

7. DISCUSSION

Ancient geometry was presented as an objective tool to expose or highlight architectural features built during prehistoric times. With no history or precedent to guide these studies, a simple though strictly scientific framework was applied to elucidate possible design traditions that may have been used in Chaco Canyon. It is not known whether the tradition was public knowledge or secreted within building guilds, though the latter is probable. Personal experience in complete rejections by many Native Americans when asked to discuss the matter seems to support the idea that such topics remain a delicate subject.

Ancient geometry was reflected in the pilaster divisions of clan kivas. The floor features and outer ring distances of great kivas were also reflected in more advance design trajectories. The geometry has provided a number of options for how the elements of the suite of floor features may have been constructed. Further investigations may elucidate which options were indeed used. Regardless of the form of geometry actually applied by the Anasazi, ancient geometry would appear to be a good tool for opening up the internal organization with the silent kivas in what was once the sacred heart of Anasazi culture.

The

unexpected revelation that Chaco Canyon had a solsticial azimuth that closely

matched the central angle of the hexagon is still being dealt with. There are

many aspects to this combination of astronomy and perfect geometry. On the other

hand, since the Anasazi are no longer around to talk to, there may be a tendency

of adding my own interpretations to something that could not be further from the

truth, i.e. adding from speculation rather than gathering from the evidence. The

pursuit is still new and perhaps as the geometry is applied by others to the

same ruins or to the hundred of other examples throughout the New World (e.g.

Paternosto 1996), another dimension of the Native American ancestors will become

clearer. The interaction between the binary symmetry pattern and the solsticial

symmetry pattern may represent such a dimensional aspect.

dealt with. There are

many aspects to this combination of astronomy and perfect geometry. On the other

hand, since the Anasazi are no longer around to talk to, there may be a tendency

of adding my own interpretations to something that could not be further from the

truth, i.e. adding from speculation rather than gathering from the evidence. The

pursuit is still new and perhaps as the geometry is applied by others to the

same ruins or to the hundred of other examples throughout the New World (e.g.

Paternosto 1996), another dimension of the Native American ancestors will become

clearer. The interaction between the binary symmetry pattern and the solsticial

symmetry pattern may represent such a dimensional aspect.

REFERENCES

Blackwell, William (A.I.A.) 1984 Geometry in Architecture Berkeley, CA: Key Curriculum Press.

Brunes, Tons 1967 The Secrets of Ancient Geometry and its Use (2

volumes) Copenhagen: Rhodos Int’l Science Publishers.

Carlson, J.B., and W. James Judge (eds) 1983 Astronomy and Ceremony in

the Prehistoric Southwest Papers of the Maxwell Museum of

Anthropology, Number 2.

Closs, Michael (ed) 1986 Native American Mathematics Austin, TX:

University of Texas Press.

El-Said, Issam, and Ayse Parman 1987 Geometrical Concepts in Islamic Art. Palo Alto, CA.: Dale Seymour Publications.

Hardaker, Chris 2001 Great Kiva Design in Chaco Canyon: An Archaeology of

Geometry Paper presented at 2001 Bridges Conference, July 26-29,

2001, Southwest College, Kansas. [To be published in 2003 Bridges

Conference Proceedings, Towson University, Maryland.]

Hardaker, Chris 1998a Chaco Canyon Kiva Geometry Paper presented at

American Anthropological Association national conference,

Philadelphia, PA. December 3-5, 1998.

Hardaker, Chris 1998b Native American Geometry website

http://earthmeasure.com.

Judd, Neil M. 1959 Pueblo Del Arroyo, New Mexico Smithsonian

Miscellaneous Collections138(1) Washington, D.C.

Judd, Neil M. 1964 The Architecture of Pueblo Bonito. Smithsonian

Miscellaneous Collections 147(1) Washington, D.C.

Kappraff, Jay 1991 Connections: the geometric bridge between art and

science. New York: McGraw -Hill.

Lawlor, Robert 1995 Sacred Geometry, London: Thames & Hudson.

Lekson, Stephen H. 1984 Great Pueblo Architecture of Chaco Canyon, New

Mexico. Chaco Canyon Studies. Publications in Anthropology 18B.

National Park Service, Albuquerque, NM.

Lekson, Stephen H. 1988 The idea of the kiva in Anasazi archaeology. The

Kiva 53(3): 213-234

Lekson, Stephen H. 1989 Kivas?, in The Architecture of Social Integration

in Prehistoric Pueblos. ed. W.D. Lipe, M. Hegmon, pp. 161-67.

Occasional Papers of the Crow Canyon Archaeological Center.

Marshall, James A. 1987 An atlas of American Indian geometry. Ohio

Archaeologist 37(2): 36-49.

McKenna, Peter J., and Marcia L. Truell 1986 Small Site Architecture of

Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. Chaco Canyon Studies, Publications in

Archaeology 18D. National Park Service, Santa Fe.

Nicholsen, Ben, Jay Kappraff, and Jay Saori Hisano 1998 A taxonomy of

ancient geometry based on the hidden pavements of Michelangelo’s

Laurentian Library. In Nexus ‘98 edited by K. Williams. Fucecchio,

Italy: Edizioni dell ‘Erba.

Paternosto, Cesar 1997 The Thread and the Stone. University of Texas

Press.

Pinxten, Rik 1987 Towards a Navajo Indian geometry. Ghent, Belgium:

Kennis en Intergratie.

Pinxten, Rik, Ingrid Van Dooren, Frank Harvey 1983 The Anthropology of

Space: Explorations into the Natural Philosophy and Semantics of the

Navajo. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Reed, Heidi E. and J. R. Stein 1998 Testing the Pecos

Classification. In, Unit Issues in Archaeology: Measuring Time, Space,

and Material ed. A.F. Ramenofsky and A. Steffen. Salt Lake City:

University of Utah Press.

Seymour, Dale 1988 Geometric Design. Palo Alto, CA: Dale Seymour

Publications.

Smith, D.E. 1951 History of Mathematics (Volume 1); New York: Dover

Publications.

Sofaer, A. 1996 The Primary Archtecture of the Chaco Culture. In Anasazi

Architecture and American Design, edited by Baker Morrow and V.B.

Price. pp. 89-132 Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Stein, John, and Stephen H. Lekson 1992 Anasazi Ritual Landscapes. In,

Anasazi Regional Organization and the Chaco System, edited by David E.

Doyel, Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, Anthropological Papers No. 5.

Stein, John, J.E. Suiter, and Dabney Ford 1996 High Noon in Old Bonito: Sun,

shadow and the geometry of the Chaco complex. In Anasazi

Architecture and American Design (draft), edited by Baker Morrow and

V.B. Price. pp.133-148. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Vivian, Gordon and Paul Reiter 1960 Great Kivas of Chaco Canyon . School of

American Research, Santa Fe.

Weigand, P.C. 1995

Architectural principles illustrated in archaeology: A case

from Western Mesoamerica. In, Arqueologia del norte y del

occidente de Mexico, ed. Barbro Dahlgren. pp. 159-171.

Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico.

Weigand, P.C. 1996 The architecture of the Teuchitlan Tradition of

the Occidente of Mesoamerica. Ancient Mesoamerica, 7: 91-101.

Williamson, Ray 1987 Light and Shadow, Ritual, and Astronomy in Anasazi Structures. In Astronomy and Ceremony in the

Prehistoric Southwest, edited by J.B.Carlson and W. J. Judge,

pp.99-119. Papers of Maxwell Museum of Anthropology,

Number 2.

Zaslow, Bert, and A.E. Dittert 1977 Guide to analyzing prehistoric

ceramic decorations by symmetry and pattern mathematics.

Anthropological research paper, No. 2. Tempe: Arizona State

University.

EarthMeasure.Com

Chris

Hardaker

2013 N. Forgeus Ave.

Tucson, AZ 85716

![]()

CIRCULAR TIMES ALTERNATIVE MAGAZINE

An International Networking Educational Institute

Intellectual, Scientific and Philosophical Studies

Copyright © 1995-2007

Website Design for the previous page of Dr. Robert M. Schoch and Circular Times

and all contents including but not limited to text layout, graphics, any and all images,

including videos are Copyright © of Dr. Colette M. Dowell, 1995-2007